From Crisis to Innovation: Mental Health Challenges from Ukraine to Syria

- Nicholas Mellor

- Dec 3, 2024

- 4 min read

Updated: Apr 7

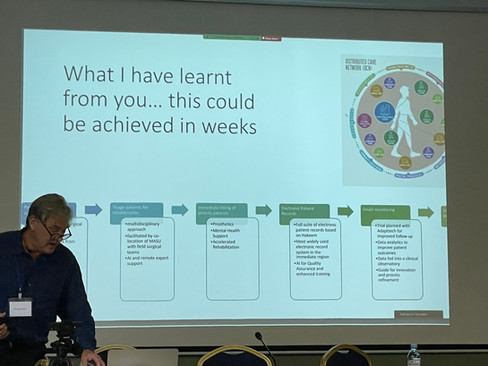

In September 2024, we delivered a paper “A Public Health Approach to Mental Health in War – Supporting Grassroots Initiatives, the Rationale, and the Role of Digital Technology" to a NATO workshop, Digital Tools for Prevention, Mitigation, and Treatment of Traumatic Stress Responses in Terror and War - Contemporary Practices and Novel Insights.

This was part of NATO's Science for Peace and Security (which supports collaboration between scientists from NATO member states and partner countries. In its Human Security Approach, NATO recognises that conflicts and crises have a significant impact on the civilian population. The Digital Tools for Prevention, Mitigation, and Treatment of Traumatic Stress Responses in Terror and War workshop

We looked for stories from countries affected by conflcit of individuals and organizations who have overcome challenges in addressing mental health trauma. The workshop focussed on Ukraine where population wide trauma is requiring an urgent need for innovation in making better psychological support more accessible and more scalable.

The psychological impact of war extends far beyond the battlefield, permeating families and communities. Different societal groups, such as veterans, widows, children, and religious leaders, experience unique mental health challenges that require tailored interventions. Traditional mental health services often struggle to meet the overwhelming demand. Resources are scarce, infrastructure may be damaged, and trained professionals may be in short supply. Moreover, the urgency of physical needs can overshadow mental health concerns.

This blog shares some of the people and stories that inspired the paper on how mental health support mechanisms can be quickly implemented and adapted to meet diverse needs in conflict-affected areas.

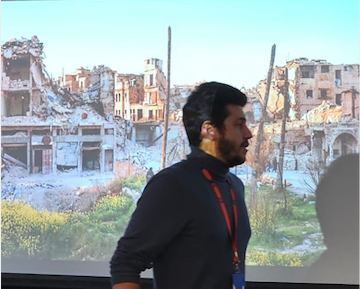

Insights from Syria

Dr Ali Mahfouz is one of the co-authors of the paper. Ali is from Aleppo, Syria, a city largely destroyed by war. He witnessed all stages of the conflict, from the peaceful revolution to the devastating fighting. He studied at the University of Aleppo Medical School (2013-2019) and, when he graduated, he worked in the Aleppo University Hospital for a year. During that time, he lost many friends, classmates, and relatives.The next few years were dominated by profound grief and the search to find new ways of using his skills as a doctor.

Empowering people is not just about finding a better way of reaching those in greatest need, but it is sometimes about helping them cope with grief, and find purpose, and build resilience. This often involves, especially in war, a more agile and adaptable approach. For instance, the very first mobile prosthetic clinic in Syria consisted of a prosthetist driving his car across the border from Turkey into Northern Syria to fit a prosthetic arm for a child. It was a breakthrough in approach: the child did not have to make the difficult journey to a clinic across the border in Turkey; the clinic came to them. This is the principle at the heart of “Restoring Hope’ in Gaza.

Insights from Ukraine

Likewise, we drew inspiration from Ukraine. We looked at innovative grassroots mental health initiatives in wartime Ukraine, highlighting the huge capacity of digital technology in amplifying effective interventions despite resource constraints. We found four essential hallmarks of successful mental health interventions in conflict-affected areas:

We found four essential hallmarks of successful mental health interventions.

1. Agility - the ability to deploy and adjust interventions quickly, including rapid training and implementation.

2. Adaptability - the capacity to modify approaches based on changing needs while maintaining cultural sensitivity.

3. Cultural Authenticity - deep integration with local practices, beliefs, and social structures.

4. Scalability - the ability to expand while maintaining quality and cultural relevance.

Case Studies

We presented five case studies demonstrating these hallmarks in action:

Moe Kolo, which provides psychological support through online sessions and workshops, combining cognitive behavioural therapy with Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. They have served over 2,600 Ukrainians, showing significant improvements in depression, anxiety, and trauma symptoms.

Supporting Wounded Veterans, which combines physical activities with digital mental health support for veterans, successfully integrating in-person activities with online interventions and demonstrating effective adaptation during COVID-19.

A network supporting Ukraine's Faith Leaders, which uses digital platforms to help pastors and chaplains serving as frontline mental health workers while dealing with their own trauma. They utilize video conferencing, mobile apps, and online training to maintain continuous support.

Lagerta, which focuses on supporting widows of Ukrainian soldiers through a three-stage digital support model, combining professional expertise with peer support and offering online learning platforms and virtual consultations.

Radooga, which serves over 1,300 children aged 5-17 across 10 cities, integrating robotics lessons with therapy sessions to support emotional healing while building technical skills.

Our research emphasizes that identifying and supporting "positive deviants" - individuals and organizations making significant impacts despite resource scarcity - can boost innovation during conflict.

We argue that when mental health initiatives encompass these core hallmarks and effectively leverage digital tools, they can successfully address mental health trauma while building community resilience.

Most important of all, it builds on the experiences of people who, like Dr Ali Mahfouz, have witnessed these challenges first hand. Dr Mahfouz shared his story with colleagues at his hospital. A story that encompassed surviving the destruction in Aleppo,the grief losing family and friends to rebuilding his resilience and sense of purpose. His key insight which he shared with his colleagues was how much helping others can help yourself.

Keep up the good work - what courageous doctor